2010 Plus Tree Cone collection for Rust-resistance Studies in Glacier NP Area of Mission Mtns Seed Zone

Project: Whitebark Pine Plus Tree Cone Collection for Rust-resistance Studies in Glacier National Park Area of Mission Mountains Seed Zone (from 2010 to 2013)

Agency/Forest or Park/District: Glacier National Park (GNP), NPS

Project coordinator: Joyce Lapp and Dawn LaFleur

Contact: Dawn LaFleur, Glacier National Park, P.O. Box 128, West Glacier, MT 59936,

406-888-7864, dawn_lafleur@nps.gov

Cooperators

Mary Frances Mahalovich, USFS Moscow FSL, will supervise rust resistance studies to be carried out at the USFS Coeur d’Alene Nursery. USFS is funding these studies. Melissa Jenkins, USFS Flathead NF, cone collection from Flathead Forest (30 trees). USFS Helena (5), Lewis & Clark (25), and Lolo (15) NF’s will also participate to reach target of 100 trees for the Missions/Glacier NP seed zone.

Source of funding /amount

FHP: $5,000 – 2010; 2011: $5,000; 2012: $5,000; 2013: $3,000

Supplemental funding: $10,000 – 2010; 2011: $20,000; 2012:$20,000; 2013: $12,500 all from park recreation funds

Dates of restoration efforts:

2010 to 2013

Objectives

– Identify healthy, apparently rust-resistant cone bearing trees (plus trees).

– Cage and collect cones from plus trees and extract seed to submit to the rust-resistance studies under supervision of Mary Frances Mahalovich, USFS.

Acres/ha treated

Collect cones from 25 plus trees to contribute seed for rust resistance studies for the Missions/Glacier Park Seed Zone.

Methods

GNP has identified more than 60 plus trees at eight different sites. To include some genetic diversity, cones are being collected from all three major drainages in the park at Preston Park in the Hudson Bay drainage, Numa Ridge in the Columbia drainage, and Scenic Point and Rising Wolf in the Missouri drainage. Another site may be added to achieve our goal of 25 trees. We will assess the status of identified plus trees and select trees to be caged in late July and cones retrieved in mid-September. With the additional funding requested this year, we will conduct blister rust surveys (following mehtods developed by Tomback et al.) in these and other stands in the park to assess the level of blíster rust present and how that has changed since 2003 when transects were last surveyed. The cones will be sent to the Coeur d‘Alene Nursery for storage and inclusion in the rust-resistance studies under the direction of Mary Frances Mahalovich.

Planting? If so, source of seedlings? Resistance? No

Outcome

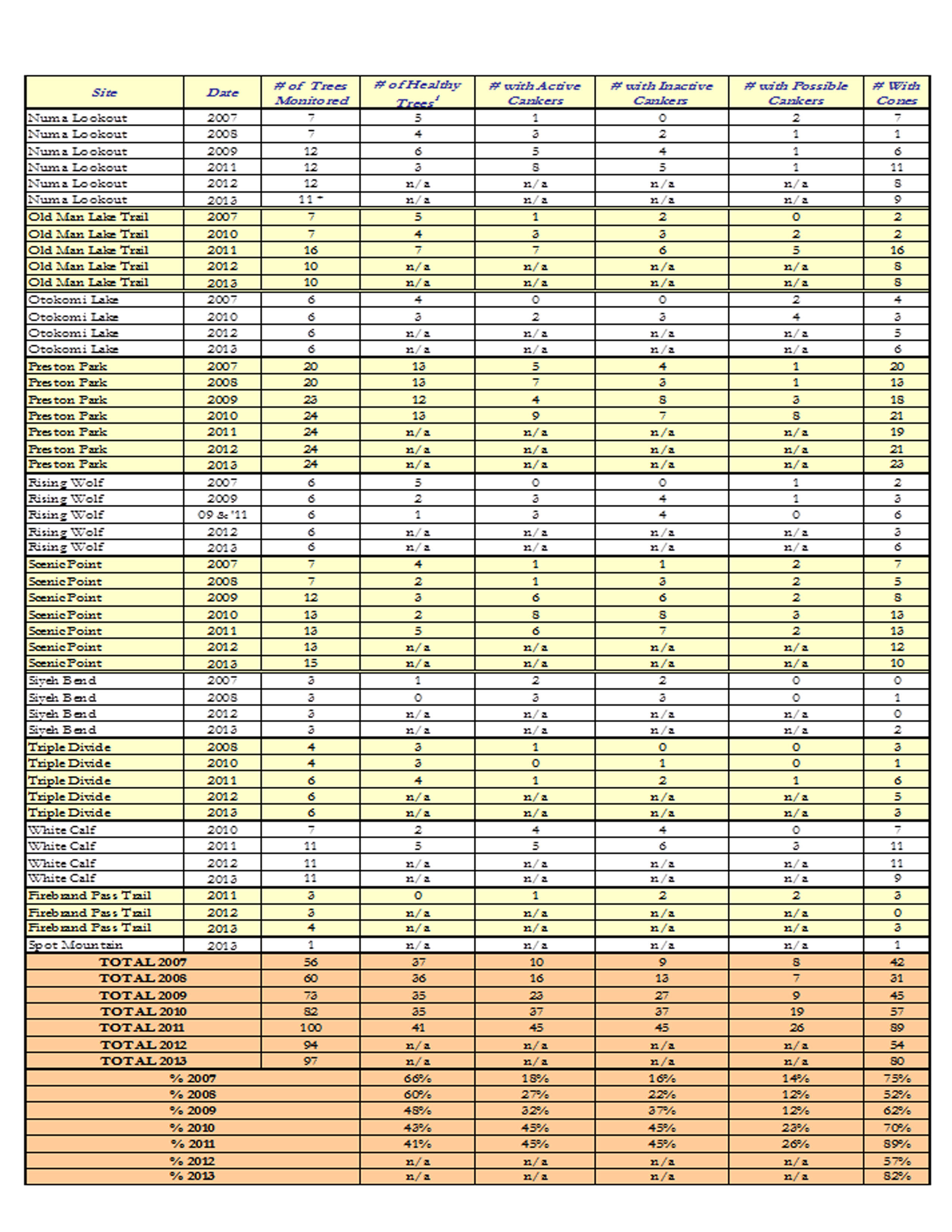

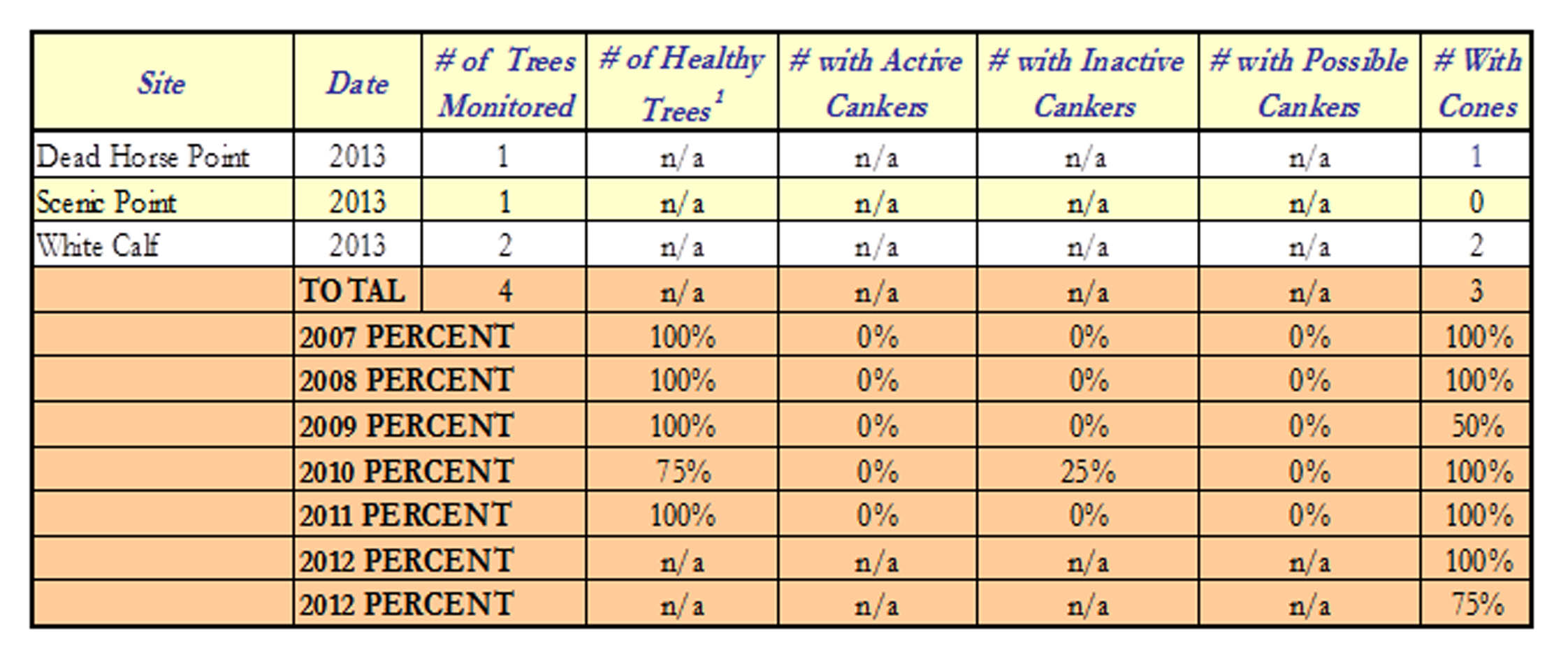

Currently, there are 97 whitebark pine trees that are being monitored as part of the plus tree pool. This is down from 100 trees that were monitored in 2011 and up from 94 trees that were monitored in 2012. From 2011 to 2012, six “potential” plus trees at Old Man were not monitored. These 6 potential plus trees need to be assessed again to decide if they need to be part of the pool. From 2012 to 2013, one plus tree died at Numa, two new trees were identified as plus trees at Scenic Point, one new plus tree was identified at Spot Mtn., and one new plus tree was identified at Firebrand Trail. Monitoring sites for whitebark pine established in 2007 include Numa Lookout (7 trees), Old Man Lake Trail (7 trees), Otokomi Lake (6 trees), Preston Park (20 trees), Rising Wolf (6 trees), Scenic Point (7 trees) and Siyeh Bend (3 trees).

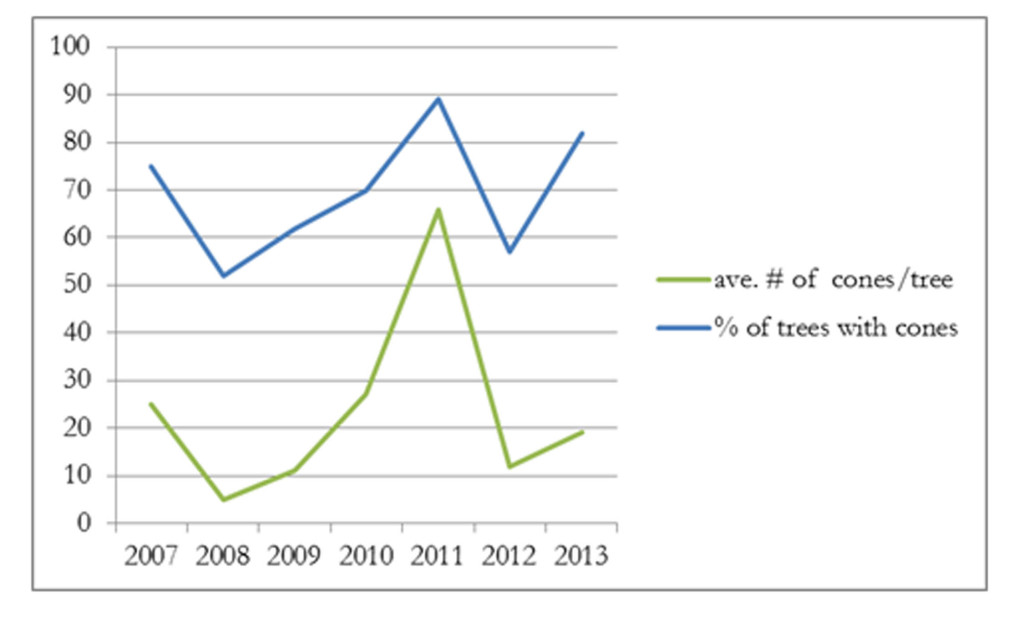

In 2008, only one site was added at Triple Divide with 4 trees. In 2009, 5 additional trees were added at Scenic Point, 5 additional trees were added at Numa Lookout and 3 additional trees were added at Preston Park. In 2010, one additional tree was added at Preston Park, one additional tree was added at Scenic Point, and 7 additional trees were added at White Calf, a new site for plus tree monitoring. In 2011, 4 new plus trees were added to the pool at White Calf, 2 new trees were added at Triple Divide Trail and 3 new trees were added at Fire Brand Trail, which is a new monitoring site. Additionally, 9 new trees were added to the pool from Old Man Lake Trail, although 6 of these trees are considered potential plus trees. Finally, in 2013, two new plus trees were added to the pool at Scenic Point, one new plus tree was added at Firebrand Trail, and one new plus tree was added at Spot Mtn., another new monitoring site. Currently, there are nine limber pine trees present in the plus tree monitoring pool. Two trees, one at Dead Horse Point and one at Scenic Point, were identified in 2007. Three additional trees were identified in 2010, two at White Calf and a second tree at Dead Horse Point. Finally, four trees, all at Spot Mtn., were identified in 2013. In 2013, due to time and money constraints, only cone counts were performed on whitebark and limber pine plus trees. This is similar to 2012. Cone counts were done at the time the revegetation crew applied verbenone patches to plus trees in the spring as well as while climbing trees for cone caging and collection.

Monitoring Results

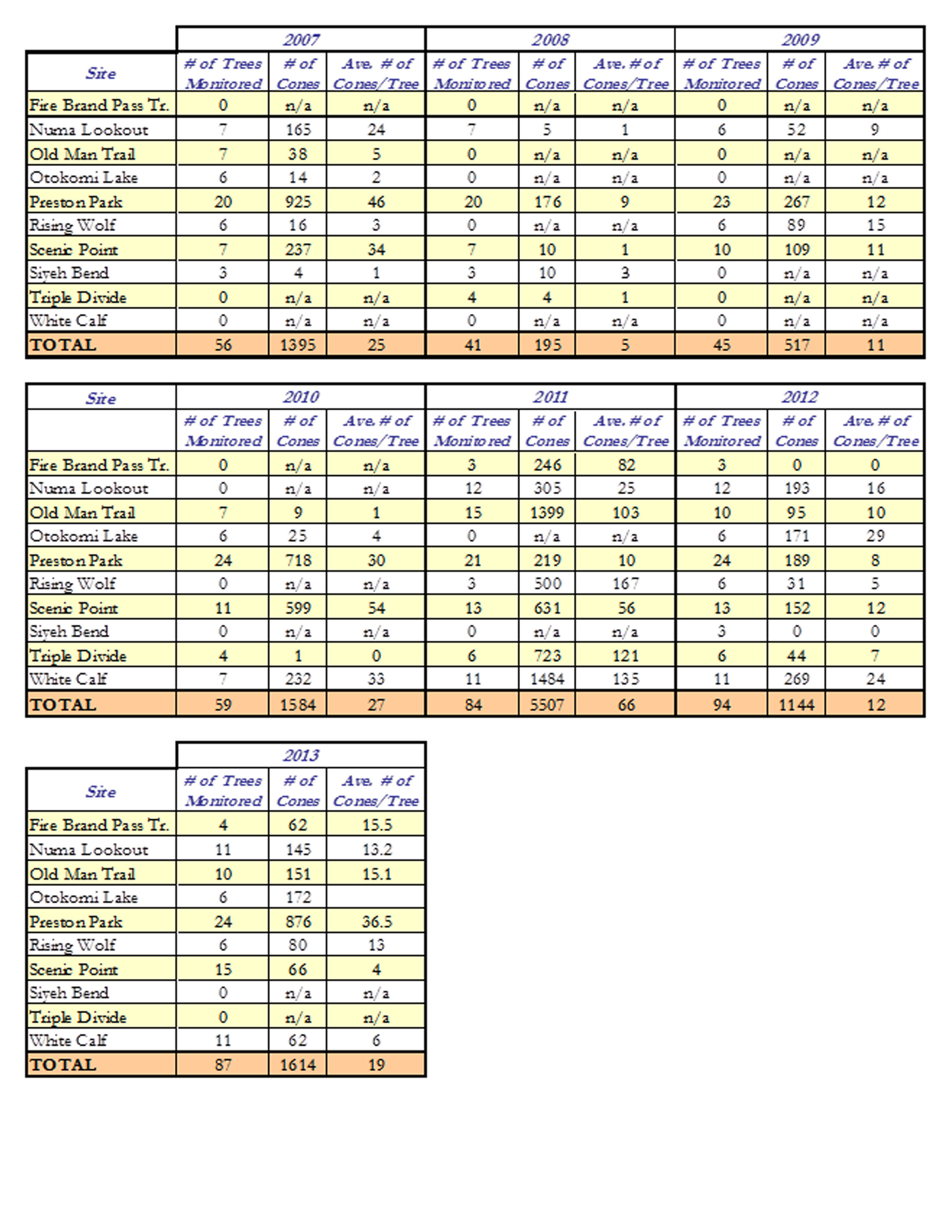

All whitebark and limber pine plus tree sites were monitored for cone production in 2013. Health of individual plus trees was not assessed this year. Cones were collected from only two trees in 2013 in order to complete the seed requirement for the rust-resistance genetics testing program with the USFS. Cone counts were performed on these trees again at this time. Since cones are much more visible when climbing a tree, cone counts increased in these trees from initial assessment in the spring. It should be noted, therefore, that cone estimates from previous years are probably about two to three times lower than the true number. For the most part, cone numbers listed in the tables below were estimated from the ground unless the tree was climbed for cone collection.

After a banner cone year in 2011, cone production dropped in 2012, only to rise to relatively high levels this year. In 2013, 82% of monitored trees produced cones, as compared to 57% last year. Despite the higher percentage of cone producing trees, the average number of cones per tree only went up slightly over last year. The average number of cones per tree was 19 this year compared to 12 average cones in 2012 and 66 average cones in 2011. Overall, this is a moderate number of cones per tree given the high number of trees producing cones. Very little is known about the frequency of mast years in whitebark pine, although it has been found that healthy stands of whitebark pine in the Greater Yellowstone area had moderate or large conecrop years 2 or 3 times from 1980-1990 (Morgan and Bunting 1990). It appears that we may be on about a2-4-year cycle, although too little data is available to make any predictions. It should be noted that the healthiest whitebark pine trees, now that they have been identified, are currently being targeted for cone collection. The actual cone production rate for the overall stand could indeed be much lower. A total of 59 cones were collected by the revegetation crew this year from two trees . This was to fulfill our seed requirement for the USFS genetic study. No seed was collected for operational purposes.

Whitebark Pine Plus Trees: Comparison of Health and Cone Production, 2007-2013.* Some of these trees have active, inactive and/or probable cankers on the same tree.

Caged Whitebark Pine Trees and Cones Collected, 2013.

| Site | Trees Cages | Cones collected |

| Otokomi | 1 | 42 |

| Firebrand Pass | 1 | 17 |

| TOTAL | 2 | 59 |

Whitebark Pine Plus Trees: Cone Frequency, 2007 – 2013.

Trends in Whitebark Pine Cone Production 2007-2013.

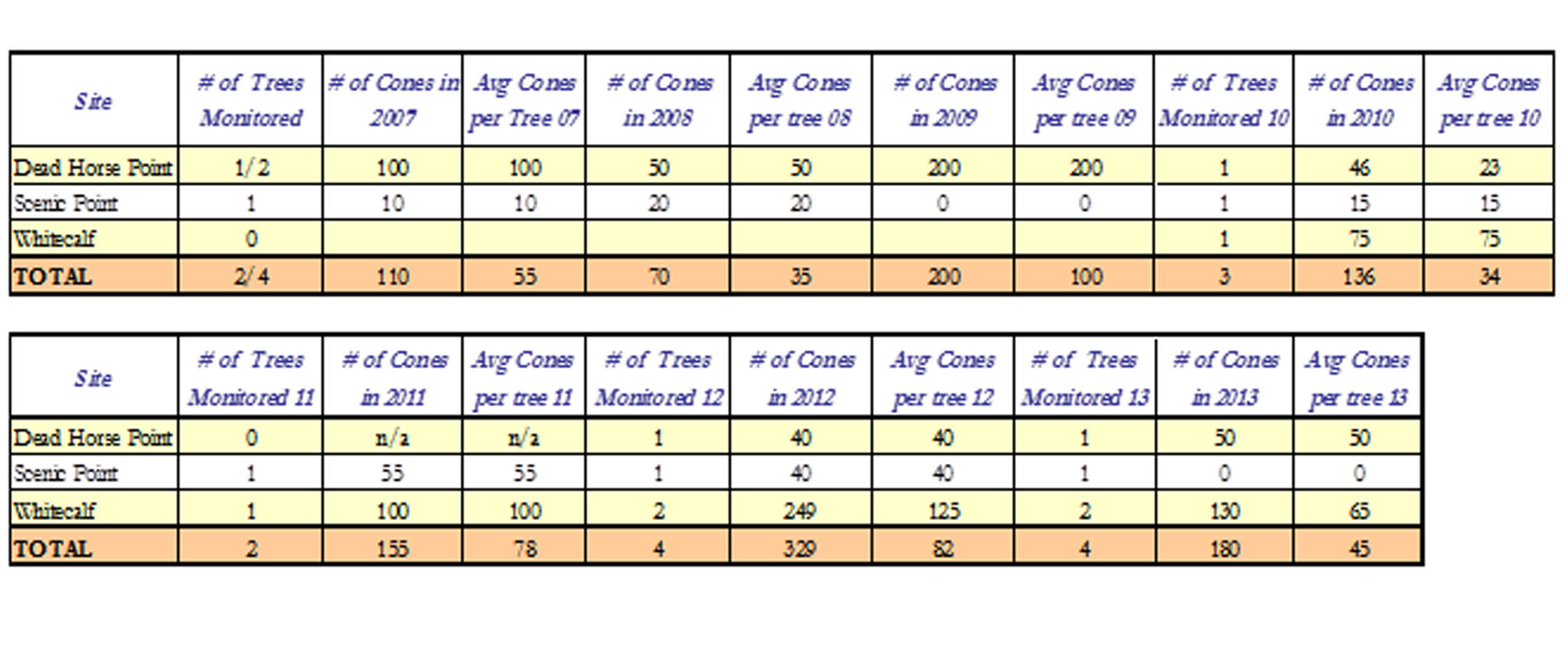

Four limber pine trees were monitored this year; one at Dead Horse Point, one at Scenic Point and two at White Calf. Each tree is healthy, although only three of the four were only a moderate number of cones this year . Average numbers of cones is lower this year than last year, although it is difficult to assess with such a small sample size. It should be noted that four additional limber pine trees were added to the plus tree pool at Spot Mountain. No cone counts or other information was documented for these trees this year so they were omitted from the data tables.

Limber PinePlus Trees: Health and Cone Production, 2013.

Limber Pine Plus Trees: Cone Frequency, 2007 – 2013.

Conclusions and recommendations

Monitoring data is beginning to document the cyclic nature of cone production in whitebark pine trees. While 2008 and 2009 showed a decline in whitebark pine cone production throughout the park, cone production was higher in 2010 at 70% and much higher in 2011 with 89% of plus trees having cones. Data from 2012 showed a decline in cone production again, similar to 2009 and 2010 levels, along with a lower average number of cones per tree. In 2013, cone production increased again to 82%, although the average number of cones per tree only went up slightly over last year, resulting in just a moderate number of cones per tree. It appears that we may be on about a 2-4-year cycle, although too little data is available to make any predictions. It is also important to note that the overall park-wide cone production was likely lower, given that the healthiest trees were targeted for cone collection and thus monitoring. Future monitoring over the next several years will begin to document the local trends of cone production in the park, as well track the impacts of increasing blister rust on cone production of the plus tree pool.

Since the future of healthy whitebark pine trees is unknown, a larger pool of trees is imperative for seed collection and genetic integrity of our seedling stock. In 2013, four new plus trees were added to the monitoring pool, including one tree along the Firebrand Pass Trail, two trees at Scenic Point, and one tree at Spot Mountain, a new site for whitebark and limber pine plus trees. There continue to be areas within known whitebark stands that could be scouted for additional plus trees, including White Calf, Preston Park, Firebrand Pass Trail, Spot Mountain, and Scenic Point. Other possible sites to search for healthy whitebark pine in 2014 include the trails in the Many Glacier subdistrict, the Morning Star Lake trail, and Bighorn Basin.

Additionally, care of currently identified plus trees continues to be a goal. Since 2008, limbs with active cankers have been removed or cut off, a recent practice that may prolong the life of certain whitebark pine plus trees in the monitoring pool. Since 2011, verbenone patches have been applied to plus trees for the in an effort to protect them from mountain pine beetle attacks. A Whitebark Pine Management Plan needs to be written to address the continued care of these trees, including protection from encroaching subalpine fire and from wildfire.

Due to time and money constraints, no data on the health of plus trees was taken this year, similar to last year. As time and money permit, health data should continue to be collected to learn more about the potential resistance of these trees. Now that more is known about varying levels of resistance to blister rust in whitebark pine trees, it is more encouraging that some infected trees may be able to remain functional for some time. The highest level of resistance is obtained when a tree contains two recessive “no spot genes”; there is no evidence these trees have been infested even after exposure. Needle shed resistance, from a single recessive gene, is another form of defense whereby blister rust spores penetrate stomates and grow down needles, but the tree is able to shed infected needles and not become further infected. A third form of defense, fascicle shed resistance, is observed when the entire 5-needled fascicle is shed after infection. A fourth form of resistance, bark reactive resistance is a polygenetic form. The bark forms a callus or “scab” and walls off the disease. This can even happen at the bole; so contrary to popular belief, bole cankers can still be present on a resistant tree. Finally, trees can still have a form of resistance while harboring active cankers that never die. As long as cankers do not girdle the tree, some trees are able to survive with one or more persistent active cankers (Maholovich pers. comm.).

This year’s cone collection should have fulfilled our requirements to enter 25 plus trees into the testing program. Information from this study will provide us with guidance for whitebark seed collection in the future and protection of our plus tree pool. In order to target our most potentially resistant trees, our current strategy for collecting whitebark and limber pine seed is to collect seed from trees that either show no or very little sign of blister rust. With the amount of energy, time and money it takes to restore whitebark and limber pine trees in the park, it seems prudent to begin the process with seed that has the best chance of restoring healthy trees to the area. Gathering long-term data on these plus trees will help to ensure that the healthiest trees in the park are being used for seed collection.

As monitoring continues, data may help to answer whether some trees that exhibit mild blister rust infection can fend off lethal infection and remain healthy. It may also help us determine a timeline for survival of trees that succumb to infection. Data may also determine whether trees that appear healthy in the midst of dead and dying trees can remain blister rust free. Monitoring plus trees should also provide data on cone production cycles that could help plan future seed collection efforts.

Whitebark and limber pine plus trees should be monitored each year if funding and time exists. Plus trees should, at a minimum, be monitored on a bi-annual basis to collect information on cone production and tree health. Additionally, it is recommended that verbenone continue to be applied to trees annually to protect against mountain pine beetle attack, which exists as a threat in the southern and northwestern edges of the park.